Going to university in the era of the internet means that a lot of class time is spent deciphering other people’s laptop screens. From the top of the lecture hall I see WhatsApp chats, intense Chess matches, NYT games, online shopping, and sometimes, GeoGuessr. For those not familiar, GeoGuesser is a game that shows you a random image of a place on Google street view, and the player tries to identify in what country the image was taken. It’s a fun but frustrating game and in the few times I’ve played it, the only real lesson I’ve learned is how much our non-urban world, actually resembles itself.

Like with most other games in this decade, there are people who have managed to make a living out of playing this game,1 in the world of GeoGuessr, Trevor Rainbolt is this person. He gained popularity for recording himself on his desk playing GeoGuessr and surprising everyone with his accurate guesses. Rainbolt was recently profiled for the New York Times, which is where I found out about him.

When I read the article, I was reminded of my Urban Planner friend, who is also chronically on Instagram and will sometimes post stories where he praises or hates on a specific public transport system, bridge design, or overall city structure, using google street view screenshots to illustrate his point. Although not going as far as Rainbolt, he once correctly guessed where I took a photo from the shape of the lampposts.2

Rainbolt is an extreme version of this, at 22 he had never left the US, and yet he could recognize images of my home country just by the shape of the blurred license plates.3 I don’t know where I stand on the debate of Google street view letting us see the world from the comfort of our homes, but what I do think, is that it can make us excessive planners, shying away from surprise and shaping us into a species that can’t deal with the unknown.

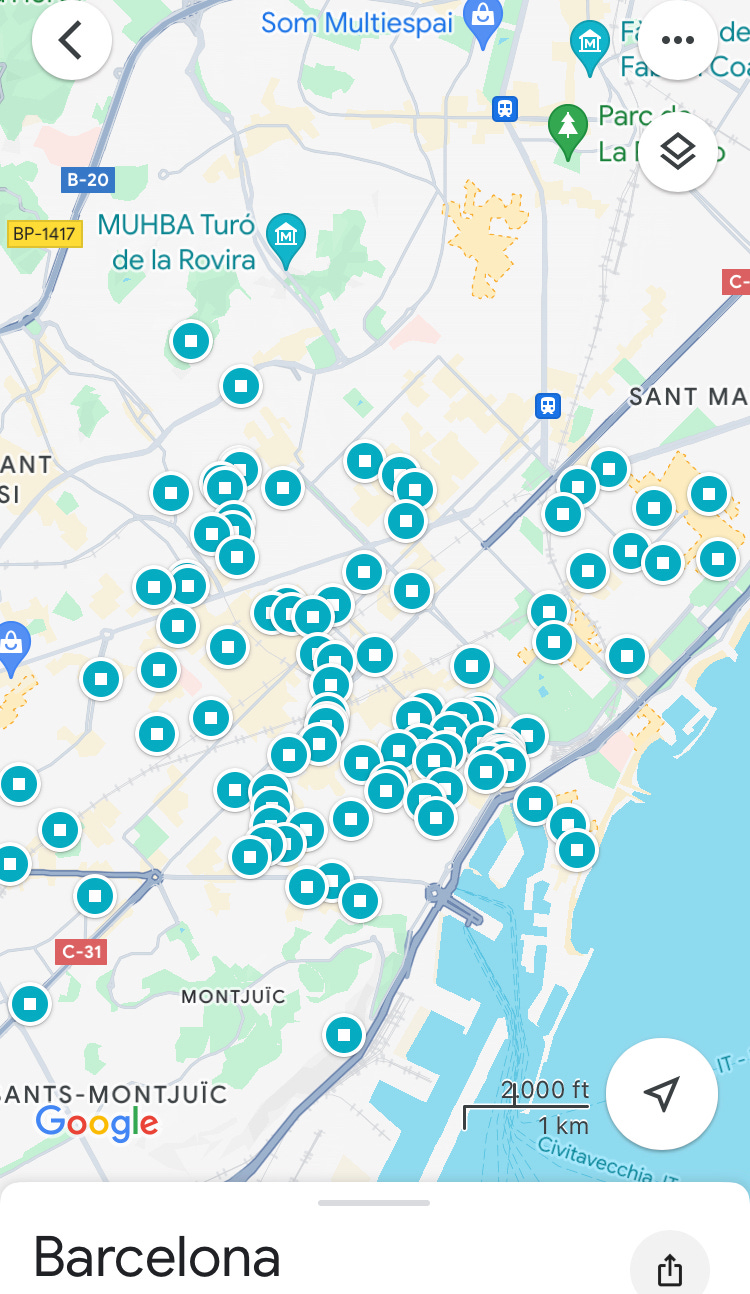

Earlier this year, while preparing for our four-day trip to Barcelona, my friend sent me a Google map database that held 150 recommendations mapped out by what the people on TikTok and Instagram thought was worth our visit.

It struck me as innately inhuman that after wandering around streets for hours, we were “afraid” to pick something that just looked good and instead chose to venture to the nearest pinned spot on the map.4 In terms of traveling, this practice reduces travel to an almost generic experience. Not only is everyone who goes to Paris seeing the same metallic structure, they are also eating and drinking at the same restaurants, shopping at the same boutiques and perhaps what’s worse, exacerbating the loop by posting the exact same activities online.

Travelling in this preformative, checklist way disappoints me. I don’t want to be able to relate to everybody’s experience, I want to create one that in twenty years will make me think, “Wow, that sword fish I had in Paris was amazing,” without being able to remember exactly where the restaurant was located.

I guess in a way, the same can be said about photography. When travelling, I too want a photo of the Eiffel Tower at golden hour, but the photos that I’m really interested in are not the postcard ones. I want to take photos that really give an insight into what daily life and culture in a different place is. Like with Google Maps pins and social media generic recommendations, that is not possible if the places I’m going to are just those that satisfy a checklist.

Under this line of thinking, I could even argue that Rainbolt might understand and know other cultures and cities better than most tourists. GeoGuesser has not only taught him about the types of bollards in different countries, but also about the different soil, flora, and fauna in different regions and cities, which can reveal a lot about the culture behind a population.

On a similar vein, photographer James Popsys, who focuses on the interplay between nature and human made objects, offhandedly remarked that he went on a trip to the Spanish town of Calpe which he found while exploring though Google street view, as he believed that the destination would be ideal for his photography practice. When I heard it, it initially gave me the same feeling that the Barcelona google map experience did, but as I thought about it, I found my opinion transforming into an appreciation for the technology. Like Rainbolt might not have ever seen a lot of the world without Google street view, Popsys would have never visited and photographed Calpe and therefore, the people he reached with his photos, would have never been impacted by them.

The fine line between the benefits of this technology and the curses of it are precarious, yes Popsys’ photos share a message of our conviviality with nature and Calpe is a great addition to his work, but the somewhat artificial research that went into his images do make them a little unnatural. In that same video, he says that he even tried experimenting on street view to find the best place to take the photo he was seeking, which echoes the behavior of the Google map-checklist trip.

I could waste my words weighing out every pro and con of the practice, but I would probably reach the same conclusion: Google Maps and street view can be great both in photography and life, but the line where they start infringing on spontaneity, creativity, and presence is incredibly thin. To try to understand the appeal further, I tried “finding” some of my own photos on street view.

In both of these cases, the location is obvious, street view clearly shows the image, especially in the second set where the subject is not a temporary walker by, but a permanent mural.

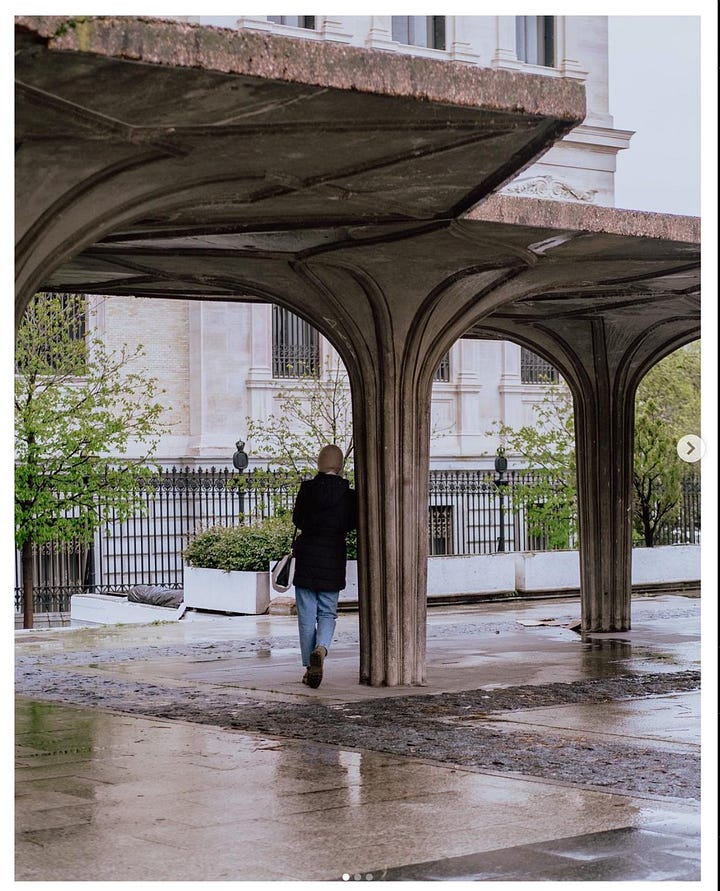

In both of these shots, the subject is more intrinsic to what makes the photo but while finding these locations, I realized that perhaps doing a little google streetview browsing, could inspire me in finding cool locations where a photo could occur (like the colorful sign or the mushroom-like structures) I also think that exploring a city like this could be a different way of seeing a hometown, commute, or place of frequent visit.

I don’t think I’ll be able to identify rural towns worldwide by the placement of their barbed wire, but I do think that James Popsys might have accidentally given me a great new tool.

- S

On a more serious note, Radio Ambulante has a great podcast episode (on Spotify it’s in Spanish, but the website has an English translation) on how currency in video games became a means to a livelihood in Venezuela’s deteriorating economy.

He had been in the city the image was taken earlier that summer — but still.

Most countries have either short or long plates, Ecuador has both.

For us, it actually wasn’t that deep — we were very present on our trip, but I know people who really aren’t.