I was at a house party, talking about the kid I sometimes babysit, when the voice of someone in attendance raised through the hiss of opening beers bottles and questionable music, and said, “So like Vivian Maier, the nanny and photographer.”

It was a friend of a friend, and I knew he meant it as 30% joke, 70% dig at me, and—thanks to his complete unawareness—0% the compliment it should have been. Which, honestly, made it even funnier.

Maier, a French-American woman, was a nanny for almost 40 years in between New York and Chicago; she never married, never had any children, and had few friends, but rather spent most of her free time photographing the cities that she lived in, often taking the children that she nannied with her. The kids described her as “a real, live Mary Poppins,” never talking down to them, and showing them life outside their affluent suburbs.1

What really made me laugh, though, was that Maier only became famous posthumously, when her work, which was acquired at an auction after she failed to pay rent on her storage unit, was acquired by John Maloof, who much later helped popularize it. In fact, despite showing a large commitment to her craft, and collecting a surprising amount of expensive cameras for the time, Maier never showed or shared her work with anyone, so someone making a joke about her, at a house party in Amsterdam, almost fifteen years after her death, is a little surreal.

In any case, it got me thinking about what Maier would have done in today’s world, where social media invades every art form with its sticky tendrils, where being a career street photographer —and woman— is easier than it was in her time. But, by the description we have of her: quiet, reserved, shy, and most important, incredibly dedicated to the craft of photography, I would bet that she would still have gotten a traditional 9-5 job and chosen an artistic photography approach over being a commercial photographer with a weekend hobby.

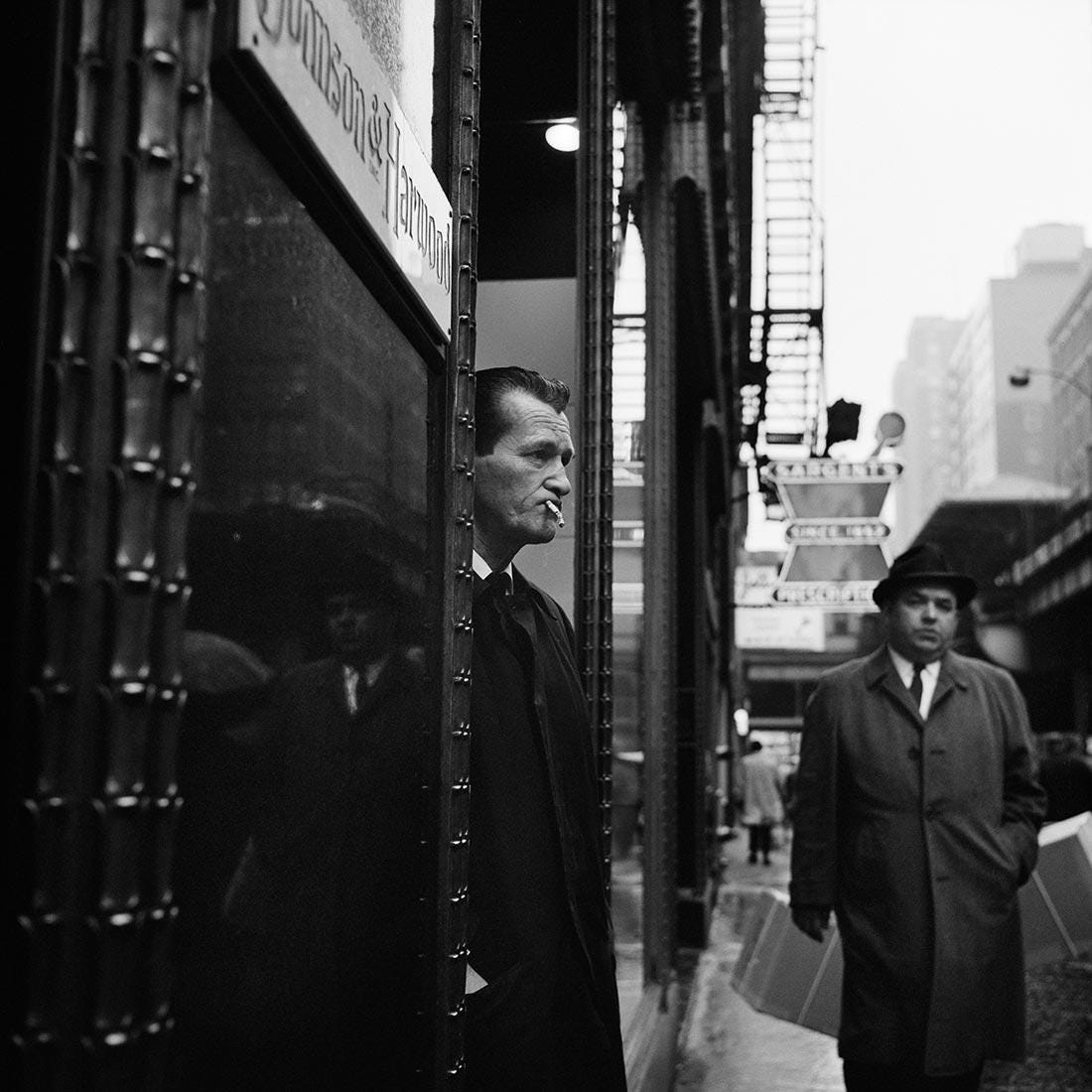

I reach this conclusion because when I look at Maier’s work, I see someone who was photographing just for herself and for the challenge of getting better. This approach leaves us with a really raw and honest documentation of New York and Chicago in the 50s though 80s, that unlike other photographers work, is not influenced by fame and public opinion. In other words, when photographing, Maier was not thinking about what people would say when her work was displayed, or shown, she was solely focused on what she found interesting and worth pursuing.

Most of her recovered work is in black and white, and she shot mainly with a Rollieflex2, which by being a medium format camera, often gave her photos a higher quality than the ones of other street photographers who preferred smaller 35mm devices due to their compact and light nature.

As a relatively shy person, the Rollieflex also gave her increased confidence, as shooting from the hip kept her intentions hidden and let her take a plethora of street portraits without the subject knowing, or reacting to the photo being taken.

Her self-portraits have also garnered a lot of attention, as they reflect a Vivian Maier drastically different from the one that people in her life knew her to be. Like many of her photos, her self-portraits are riddled with humor and creativity, which contrast the stark seriousness and privacy she was known for.

While scouring her archive, I also learned that her shadow was a subject that she frequently photographed, and that later, when cataloguing, Maloof and others decided to place under self-portraits.

In these hidden portraits, her figure is clearly visible, and although it’s just a shadow, her bent arms at the waist, clearly signal her signature camera holding pose. Aspects, like the recognizable pose and evident humor, infuse Maier’s work with her personality, which in my opinion is part of the fuel that made her deeply intriguing and therefore helped lit the fire of her fame after death.

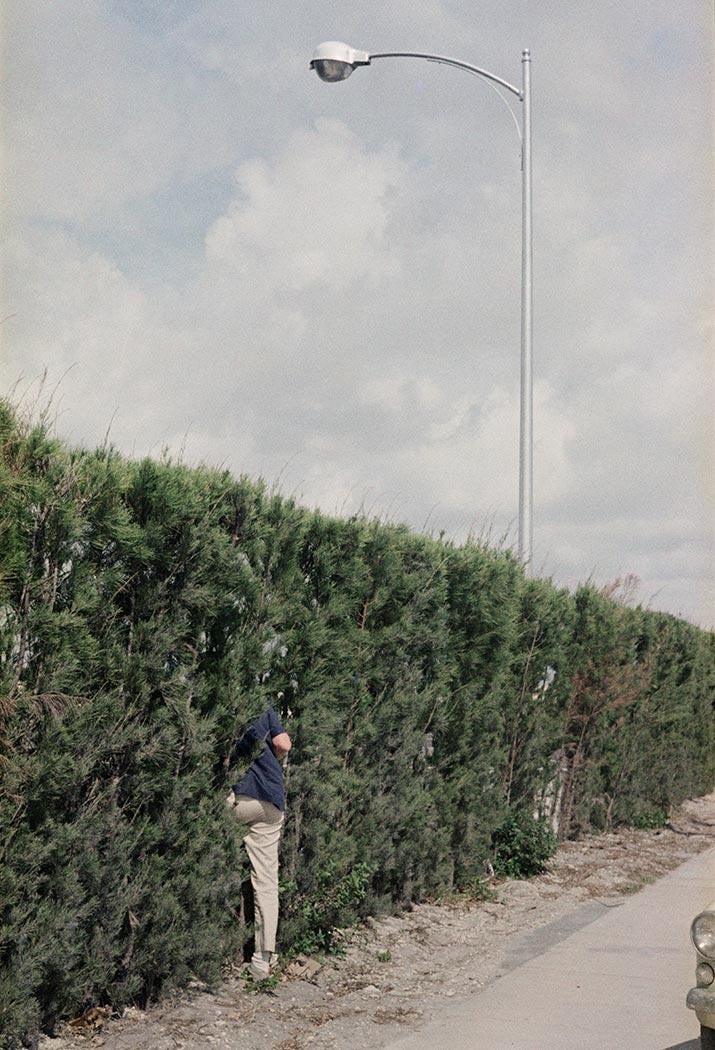

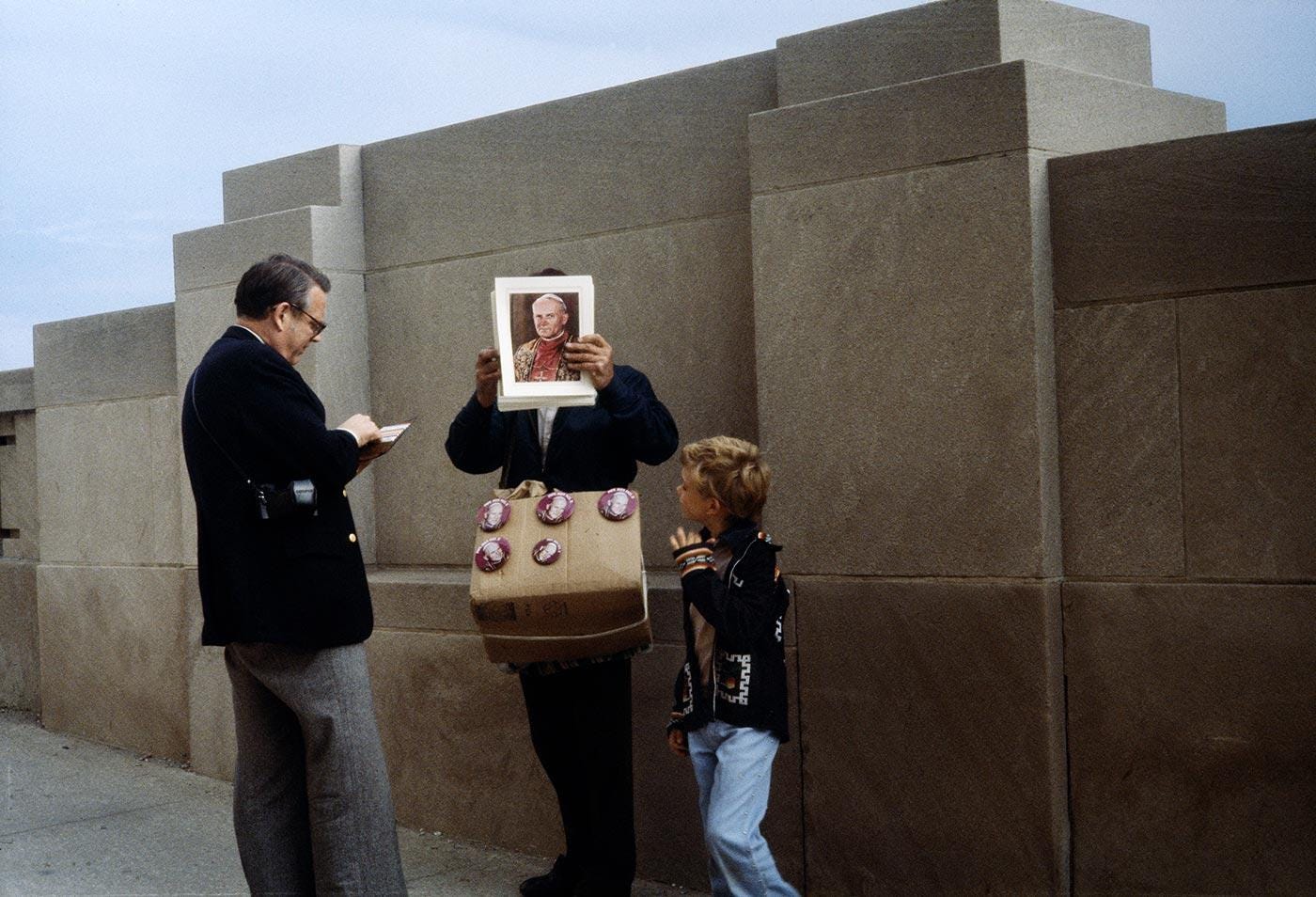

Most of her archive is black and white, but the color work—my favorite—came later. It’s different. Looser, more playful. The same sharp eye, but with an even greater sense of experimentation.

Going back to Maier’s name floating around a house party full of 20-somethings who were in diapers when her work was discovered, it’s hard to reconcile the ethics of how it was unearthed with the impact she’s had on photography. Her work has become a beacon for women photographers, often shut out of the male-dominated field. And by never selling a single print, by keeping a separate job her whole life, she redefined what it even means to be a “professional” photographer.

The publicity of her work will always be a violation of her privacy, but it’s also what keeps her images alive. I can add my voice to the hundreds speculating about what Maier meant, what she intended. I can search for meaning in her choices, and wonder if she would be glad that those color photos—the ones that feel most like glimpses into her world—have stayed a little more in the dark.

But in the end, I want to believe that although she’s not the one that economically profited from the fruits of her years long photographic practice, she’s the one that got the last laugh, as there are certain truths Maier took with her—secrets she left sealed in negatives, never meant to be exposed.

I’ll see you next week,

S

Eventually, as she aged, children that she babysat took care of her when she could no longer pay her rent.

Again shows large amounts of commitment because Rollifex cameras were very expensive, especially for a nanny

Wonderful article! I too often wonder what she would think about her discovery and fame.

This is great!